[soundcloud url=”http://ift.tt/1TG1uvn”]

Category Archives: Blog

The Manchester Ballads

The Manchester Ballads is a collection of thirty five broadside ballads dating from the time of the industrial revolution. Collected by two local historians and folk music enthusiasts, and published with financial help from the education offices at Manchester City Council, The Manchester Ballads was produced in a handsome hardback card case, and is in the form of a folio collection of loose- leaf facsimile prints of the original penny broadsheets. There is accompanying text with many of the ballads, giving the biography of the song and, where necessary, a glossary of dialect terms. There are tunes suggested to allow the ballads to be sung communally in pubs and at home, and whilst penny broadsides were produced in the hundreds, many were written to be sung to well known tunes. The impoverished audience would, with few exceptions, have no ability to read music (Boardman and Boardman 1973) and many would also be totally illiterate, only learning the songs through the oral tradition of singing in pubs, at markets and in local homes.

The Manchester Ballads are, in essence, a snapshot of Mancunian life in the industrial era. However, they are a snapshot from a very selective source, and the themes, events, places and characters that are outlined within the lyrics of the ballads should be seen in the context not only of their chance survival, but also of the reasons for publication.

The themes in the Manchester Ballads speak of struggle (The Spinners Lamentation 1846), poverty (Tinkers Garden 1837), civic uprisings (The Meeting at Peterloo 1819) and communal tragedy (The Great Flood 1872). However, they also recall good nights out (Victoria Bridge on a Saturday Night 1861), day trips around the region (Johnny Green’s Trip fro’ Owdhum to see the Manchester Railway 1832) and the various innovations and achievements of industrial Manchester are mentioned, and praised, throughout.

Manchester’s Improving Daily

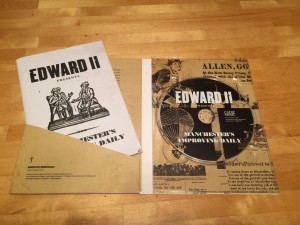

In February 2016, English roots musical collective Edward II released ‘Manchester’s Improving Daily‘, a collection of rare and historic songs, known as the Manchester Broadside Ballads, dating back over 200 years to the Industrial Revolution.

Beautifully designed, packaged and presented, the physical CD is the culmination of a 15-month project, ‘Manchester’s Improving Daily’. The CD is accompanied by a book, written by social archaeologist David Jennings and explains the history of the songs and provides an informative commentary to these rare glimpses into the lives of working class Mancunians in the Victorian times.

The CD is distributed through Cadiz Music and can be ordered through any good record store, this website and all main digital outlets. Physical copies only will include the book about the broadsides.

Ordering info:-

Artist: Edward II

Distributor: Cadiz Music

Album Title: Manchester’s Improving Daily

Catalogue No. E2MID1819

The Great Flood

[soundcloud url=”http://ift.tt/1QUfSjK”]

The Execution of Allen, Gould & Larkin.

One of the most harrowing stories recorded in the Broadsides, was the execution of the three members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood,William Philip Allen, Michael Larkin, and Michael O’Brien. In the attached image from the time, O,Brien was named Gould.

‘ They were executed for the murder of a police officer in Manchester, England, in 1867, during an incident that became known as the Manchester Outrages. The trio were members of a group of 30–40 Fenians who attacked a horse-drawn police van transporting two arrested leaders of the Brotherhood, Thomas J. Kelly and Timothy Deasy, to Belle Vue Gaol. Police Sergeant Charles Brett, travelling inside with the keys, was shot and killed as the attackers attempted to force the van open by blowing the lock’.

Wikipedia

Peterloo

The growing urban discontent that led to the infamous meeting in 1819, like other occasions of civil unrest covered in the Manchester Ballads, grew out of a combination of circumstances that, seen in hindsight, were almost bound to end in conflict.

On the 16th August 1819, the area around St Peters Square in Manchester was the site of a peaceful protest that ended in bloody confrontation with the authorities. Quickly dubbed ‘Peterloo’, the name is a satirical comment on what was seen as the cowardly actions of the soldiers and yeoman who attacked unarmed civilians. By using the term Peterloo, protesters and social commentators were mocking the troops with a name redolent of the famous battle at Waterloo, where the bravery of men was taken for granted, and a matter of national pride. Peterloo, in contrast, was seen by most as a matter of national shame. The speakers platform had banners arranged that read

“REFORM, UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, EQUAL REPRESENTATION

and LOVE”

however, events on the day prove just how hard the fight was for the working classes in industrial Manchester and Salford.

The French Revolution of 1789 was still in the minds of many radicals in England, and the word of various activists added to the unease that many workers felt under the increasingly dominant and often abusive grip of the factory owners. Thomas Paine’s rhetoric was typical, and captured hearts and minds across the working classes.

EDWARD II needs YOU!

Are you friends on our edwardthesecond Facebook page, read the website or been to one of our gigs our pop up events this summer? If so, please click on the link and complete our survey.

Only 10 questions and less than five minutes to complete, please let us know what you think!

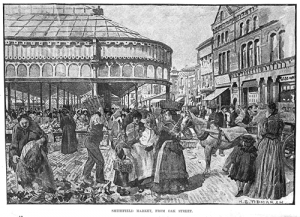

Smithfield Market

(Taken from the Band on the Wall archive which was originally called the George & Dragon)

In 1820 came the single, most important development that in large measure would underpin the viability of the George & Dragon – and indeed the economy of the immediate area – for 150 years. This was the move of the markets to the gardens to the east of Shudehill and their subsequent expansion on a grand scale – eventually totalling over four acres – directly behind the pub. Virtually overnight the George & Dragon had become a market pub.

First came the potato market, then Acres Fair – a farmers market that had been in existence for 650 years at Acresfield, now the site of St Ann’s Square – followed by the butchers and greengrocers from the New Cross shambles and then the meal and flour market. Within two years it was officially given the title of Smithfield Market – and in the next three decades would become one of the biggest in Europe. A significant factor in its expansion was the completion in 1839 of the Rail Station, 400 yards away in Oldham Road – exclusively a goods station from 1844. Horse-drawn and hand carts would take produce to and from the market, and several warehouses were constructed at the station for the storage of, for example, fruit, vegetables, fish, potatoes and grain. The station closed in 1968; the market would follow within five years.

For the George & Dragon and for many small businesses and individuals, directly or indirectly dependent on the textile industry, the arrival of the markets must have done much to soften the impact of the slump in the textile industry of 1825 and, indeed, to survive the ravages of subsequent deep recessions, pestilence and plague.

No doubt all now vying for the drinks trade from the Market, there were other, older pubs in the immediate vicinity, including the Hare & Hounds, Shudehill, the Fleece and the Wheatsheaf, both on Oak Street, and the Swan with Two Necks, Withy Grove. The competition for this trade must have hotted up when, on the same Swan Street block as the George & Dragon, two more pubs opened for business and both are still operating: the Smithfield Market Tavern, in 1823 – now the Smithfield Hotel – and The Grapes (1826), now the Burton Arms Hotel, next door to Band on the Wall. As the Market grew in size and significance, other pubs sprung up including the Man in the Moon on Coop Street and the Spread Eagle on Eagle Street – on part of the site now occupied by the Royal Exchange Theatre’s workshops, costume department and rehearsal rooms in Swan Street.

Despite the competition, or perhaps because of it, the landlord of the George & Dragon acquired the attached property in Oak Street and by 1828 it was listed as part of the pub, though it would be into the 20th century before the two properties were connected internally. This was the first of a number of expansionist moves by the George & Dragon over the years; this history of the physical evolution of the building, leading to the development of Band on the Wall, is traced in more detail in Chapter 4, The Buildings.

It was not just the George & Dragon that looked to expand. In 1829 the Smithfield Market Tavern comprised a grocer’s shop on the Swan Street corner – probably originally occupied by loom-maker Thomas Coop – and the adjoining tavern and brewhouse in Coop Street. Licensee Isaac Middleton converted the shop into a vault and installed a bar counter some eight yards long13. The expansion might not have been entirely successful, as by 1850, the Smithfield Tavern shared the address with a fishmonger, presumably trading from the front shop.

Poster pdf’s now available on the site

You can now view, download and save the posters we created for the pop-up shows in Manchester.

To see this content click on either of the links below

http://edwardthesecond.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/broadsides_a3s.pdf

http://edwardthesecond.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/broadsides_a2.pdf

Broadside Ballads – A brief history

Broadside Ballads are printed versions of popular song that were distributed for in the towns and cities of England for hundreds of years.

“The Ballad originated in collective worksongs. People orking together at some rythmic activity… frequently sang both to keep in time in their work and to lighten the burden” (Palmer1980: 9)

The national collection of Broadside Ballads exists across disparate collections that have been held across the UK, often for hundreds of years, by libraries, universities and other institutions. Comprising of songs that were often collected by just a few individuals who, with immense foresight, took the time to visit local singers and also collected paper copies of the penny broadsheets printed regionally. These institutions have acquired and stored a social resource that, when considered as a national collection, unwittingly forms a wealth of cultural and historical knowledge, as represented by the places, stories and characters with the ballads.

By repeatedly using well-known tunes, the songs could reach a wider audience. This also meant that publishers could pay ‘hack writers’ to add new words to existing music, saving money on the production costs as composers were rarely employed. The earliest song in The Manchester Ballads collection dates from 1785, the latest 1882, although within the wider collection of broadside ballads there are printed versions of songs that date back to 1550, and many are thought to be derived from folk songs passed down through the oral tradition for many years before they were ever printed. The earliest surviving collection of Ballads dates from 1556, and is called “ A handful of Pleasant Delights”.