Heaven knows I’m miserable now : Mancunian Social Identity portrayed in the arts.

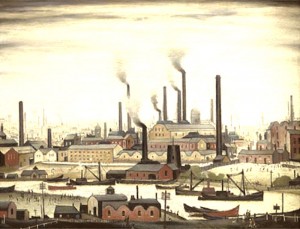

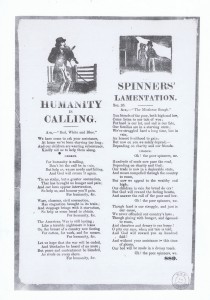

The paintings of LS Lowry are perhaps one of the best known examples of art reflecting northern life in the dying days of heavy industry. Lowry painted what he saw first hand, often producing subdued images of “faceless figures, over-sized factories, underfed bodies and drab housing” (Winterson 2013) that evoke the poverty and deprivation common across Salford and Manchester.

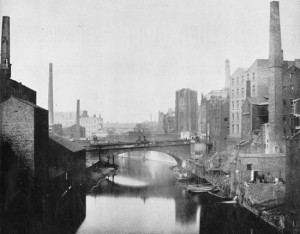

Seen through the eyes of twenty first century Britain, the protagonists in these artistic depictions live in a different world, and yet they are often walking the same streets, using the same buildings and doing the same jobs. Recent excavations in the city centre have revealed remains of the conditions Lowry depicted. Sites at Birley Fields, Angel Meadow, Danzig Street and Salford

Crescent have all revealed the remains of the slum housing that blighted the lives of workers during the industrial revolution.

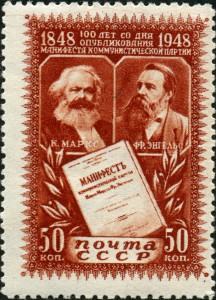

It is well known that the works of Marx and Engels are rooted in the conditions they observed whilst living in the Angel Meadow area of Manchester, and Engels despaired at the slum housing and harsh conditions endured by Mancunians when he wonders how “such a district exists in the heart of the second city of England, the first manufacturing city in the world.”(Engels 1846: 65).

Most of the buildings from this era have been lost to gentrification, development and demolition, but where they remain they provide evocative indicators of the way social identities were played out. In public spaces, this was via the demarcation of clear – and often clearly labelled – social spaces such as markets and licensed premises.

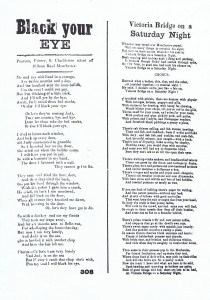

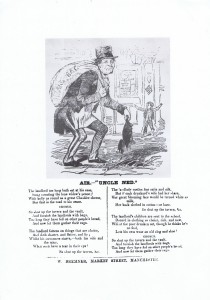

The Angel Inn, on the edges of Manchester’s trendy Northern Quarter, is a perfect example. Although much altered and rebuilt since the Angel Inn of the eighteenth century, this is the site of the pub that is mentioned in the 1859 version of ‘The Soldiers Farewell to Manchester’, the first broadside in the Manchester Ballad collection. Today, the Angel Inn stands in the middle of the area dominated by the new ‘Noma’ development by the Co-operative group, with apartments and plush office blocks now surrounding the pub.

When the Angel Inn was opening, it appears that Swindels Printers were commissioned to print a partially re-written version of a much older song as a form of advertising for the opening (Reid 15).

The message within the ballad is clear – The Angel Inn is the place to meet the prettiest girls in Manchester. The rest of the song is a variant on a common theme, with a girl vowing to wait in chastity for the return of her true love.