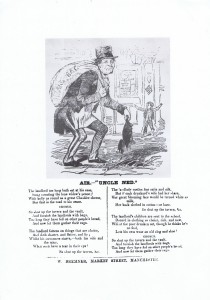

The Manchester Ballads is a collection of thirty five broadside ballads dating from the time of the industrial revolution. Collected by two local historians and folk music enthusiasts, and published with financial help from the education offices at Manchester City Council, The Manchester Ballads was produced in a handsome hardback card case, and is in the form of a folio collection of loose- leaf facsimile prints of the original penny broadsheets. There is accompanying text with many of the ballads, giving the biography of the song and, where necessary, a glossary of dialect terms. There are tunes suggested to allow the ballads to be sung communally in pubs and at home, and whilst penny broadsides were produced in the hundreds, many were written to be sung to well known tunes. The impoverished audience would, with few exceptions, have no ability to read music (Boardman and Boardman 1973) and many would also be totally illiterate, only learning the songs through the oral tradition of singing in pubs, at markets and in local homes.

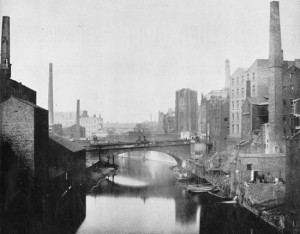

The Manchester Ballads are, in essence, a snapshot of Mancunian life in the industrial era. However, they are a snapshot from a very selective source, and the themes, events, places and characters that are outlined within the lyrics of the ballads should be seen in the context not only of their chance survival, but also of the reasons for publication.

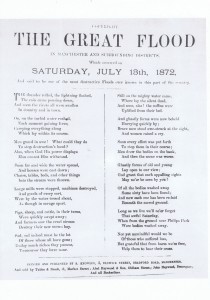

The themes in the Manchester Ballads speak of struggle (The Spinners Lamentation 1846), poverty (Tinkers Garden 1837), civic uprisings (The Meeting at Peterloo 1819) and communal tragedy (The Great Flood 1872). However, they also recall good nights out (Victoria Bridge on a Saturday Night 1861), day trips around the region (Johnny Green’s Trip fro’ Owdhum to see the Manchester Railway 1832) and the various innovations and achievements of industrial Manchester are mentioned, and praised, throughout.