(Taken from the Band on the Wall archive which was originally called the George & Dragon)

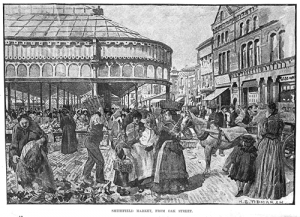

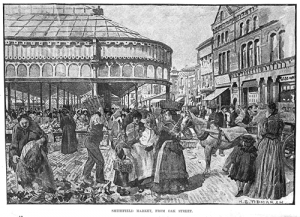

In 1820 came the single, most important development that in large measure would underpin the viability of the George & Dragon – and indeed the economy of the immediate area – for 150 years. This was the move of the markets to the gardens to the east of Shudehill and their subsequent expansion on a grand scale – eventually totalling over four acres – directly behind the pub. Virtually overnight the George & Dragon had become a market pub.

First came the potato market, then Acres Fair – a farmers market that had been in existence for 650 years at Acresfield, now the site of St Ann’s Square – followed by the butchers and greengrocers from the New Cross shambles and then the meal and flour market. Within two years it was officially given the title of Smithfield Market – and in the next three decades would become one of the biggest in Europe. A significant factor in its expansion was the completion in 1839 of the Rail Station, 400 yards away in Oldham Road – exclusively a goods station from 1844. Horse-drawn and hand carts would take produce to and from the market, and several warehouses were constructed at the station for the storage of, for example, fruit, vegetables, fish, potatoes and grain. The station closed in 1968; the market would follow within five years.

For the George & Dragon and for many small businesses and individuals, directly or indirectly dependent on the textile industry, the arrival of the markets must have done much to soften the impact of the slump in the textile industry of 1825 and, indeed, to survive the ravages of subsequent deep recessions, pestilence and plague.

No doubt all now vying for the drinks trade from the Market, there were other, older pubs in the immediate vicinity, including the Hare & Hounds, Shudehill, the Fleece and the Wheatsheaf, both on Oak Street, and the Swan with Two Necks, Withy Grove. The competition for this trade must have hotted up when, on the same Swan Street block as the George & Dragon, two more pubs opened for business and both are still operating: the Smithfield Market Tavern, in 1823 – now the Smithfield Hotel – and The Grapes (1826), now the Burton Arms Hotel, next door to Band on the Wall. As the Market grew in size and significance, other pubs sprung up including the Man in the Moon on Coop Street and the Spread Eagle on Eagle Street – on part of the site now occupied by the Royal Exchange Theatre’s workshops, costume department and rehearsal rooms in Swan Street.

Figure 8 – The block as it currently stands

Despite the competition, or perhaps because of it, the landlord of the George & Dragon acquired the attached property in Oak Street and by 1828 it was listed as part of the pub, though it would be into the 20th century before the two properties were connected internally. This was the first of a number of expansionist moves by the George & Dragon over the years; this history of the physical evolution of the building, leading to the development of Band on the Wall, is traced in more detail in Chapter 4, The Buildings.

It was not just the George & Dragon that looked to expand. In 1829 the Smithfield Market Tavern comprised a grocer’s shop on the Swan Street corner – probably originally occupied by loom-maker Thomas Coop – and the adjoining tavern and brewhouse in Coop Street. Licensee Isaac Middleton converted the shop into a vault and installed a bar counter some eight yards long13. The expansion might not have been entirely successful, as by 1850, the Smithfield Tavern shared the address with a fishmonger, presumably trading from the front shop.